Intellectual Disability

On this page:

About intellectual disability

Students with intellectual disability find it harder to learn, which means they need extra time and help to learn new skills. While intellectual disability can look different from one student to another, students with intellectual disability may experience differences in their:

- Thinking and organisation. Students with intellectual disability will typically experience difficulties in some form with thinking skills, such as attention, reasoning, problem solving, memory, planning, and judgement (e.g. understanding and predicting risks). This can impact the speed or way in which they best learn, and they tend to need extra time and help to learn new skills or knowledge (e.g. reading, maths). Some students may be easily distracted and need support with organisation, or they may find instructions with several steps hard to follow. Students with intellectual disability often prefer concrete learning tasks, and multi-modal or hands-on learning tasks.

- Communication and social skills. Students with intellectual disability may seem socially immature for their age, and they may find it difficult to understand body language (e.g. facial expression, gestures). Some students might have lots of language and others might only use a few words or no words.

- Emotions and behaviour. Some students can find it challenging to manage their emotions and behaviour, or to recognise and respond to the emotions of others. Some students may be gentle and calm, while others may become frustrated or distressed and engage in challenging behaviours. Students with intellectual disability may experience low self-confidence or depression, anxiety or frustration if they consistently find they are unable to complete a task or have their needs met.

- Practical skills. Some students may need support and lots of opportunities to practise practical skills, such as dressing, eating or toileting, or telling the time and handling money.

- Health and movement. Some students may tire easily, particularly when there are many demands on them. They may find some motor skills difficult. Some may also be restless, or over-active.

Strengths

What might be some strengths?

- Teenagers with an intellectual disability may find is easier to remember visual information, such as written letters or numbers, and pictures. This may mean that work presented visually may help some teenagers learn.

- Similarly, teenagers with an intellectual disability may be able to recognise words, letters and numbers and name them aloud. This may mean that some teenagers with an intellectual disability are able to read words that rely more on recognition than on ‘sounding out’.

Where might you provide support?

- They might need more time to think and understand. They might not understand instructions if they are given a lot of information at once.

- They may take longer to learn new skills. Structure and routine may help them.

- They can be very social and friendly, and like talking and spending time with other people. However, sometimes, they might stand too close or be overfamiliar with people.

Evidence-based strategies

Consider adjustments to communication style

Consider adjustments to activities and rules

Work collaboratively

Build social skills

- Get student’s attention before communicating. When giving instructions or talking with students make sure you have their full attention before beginning. This can be done out loud or with a gesture.

- Be clear and specific. It can be helpful to give clear and specific instructions about the task or behaviour expected, and how much time they have to work in.

- Use visual instructions. Visual instructions about a task or behaviour may help support some students. Consider demonstrating the task/behaviour, or asking another student to demonstrate. You could also use a visual schedule, poster or video to outline or model the task. Some students may find it easier if they can use gestures. Some students may need to point to the correct answer instead of talking.

- Tailor tasks to engage students. Tailor tasks for the student’s current level of understanding so they can achieve success and build from there.

- Give students lots of time to practise. Offer fewer tasks with more time to practise instead of many tasks with little time to practise.

- Have a consistent routine. Routines help a student understand how to behave. Students often feel more secure when they know what to expect.

- Embed learning opportunities and instructions across the naturally occurring routine of your classroom. Identify specific times and activities to provide instructions. Examples include when students are taking a break from or transitioning between activities.

- Use systematic instructions. Divide learning into smaller, sequential steps with lots of repetition. Plan lessons to progress from easier to more difficult content and tasks. Break harder skills into smaller, more manageable steps. Present students with similar types of questions and activities until they show the target level of mastery, before progressing to the next level. Use prompts and feedback to maximise the chances of students performing the target skill. Provide encouragement and recognition of their efforts.

- Consider using time delay programs or approaches. These are questions or problems that have a set amount of time for the student to answer. When the time is up, the correct answer is given.

- Use simultaneous prompting. Present prompts (assistance/cues) at the same time as instruction. Provide corrective feedback if a student makes an error. Encourage students for correct responses.

- Adjustments to reading materials. Provide materials that are age-appropriate, and suitable for the reading level of a student. Using audiobooks and providing choices may support their engagement.

- Allow students to demonstrate understanding in multiple forms. Students can demonstrate understanding in ways that align with their strengths and abilities. For example, by making a poster, presentation or written report.

- Provide plenty of opportunities for students to work together. Students with and without an intellectual disability can get to know each other and build friendships through working together. This also helps students learn through watching others.

- Allocate specific tasks within the group. Consider assigning tasks so that a student with an intellectual disability can use tailored materials or instructions if needed.

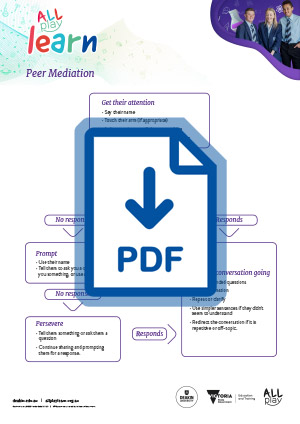

- Provide support to promote communication and interaction between peers as needed. For example, consider teaching students interaction strategies and social-communication skills (e.g., through instruction and modelling), prompting interactions, facilitating group dynamics, and providing praise for target behaviours.

- Encourage peers to provide academic and social support.

- Help students develop their social skills. Target skills may include speaking and listening, asking questions, and understanding and expressing emotions. Consider using a combination of video modelling, social stories, and roleplaying activities to teach these target skills.

- Teach students to express their needs and wants. Use prompting, video-modelling, and roleplaying to teach students to request items, activities, or assistance. Arrange the environment and identify students' interests and preferences to motivate and reinforce their efforts. Encourage students to use whichever mode of communication is most appropriate (e.g., picture cards, objects, writing, speech).

View an example demonstrating how a teacher can use a strengths-based approach to apply evidence-based strategies to support a student with intellectual disability.

Best practice tips

Provide a supportive environment

Reduce background noise when giving instructions

Ask parents

Teach self-management strategies

Promote self-determination

Use errorless learning procedures

- Students might lack confidence and may worry that they will not be able to keep up with other students. Praise efforts and encourage participation.

- Use our anxiety resource toolkit to recognise and support student anxiety.

- Avoid background noise and distractions while giving instructions to help all students hear and focus on you. You might need to face the students away from distractions behind you.

- Talk to parents to find out the best way to communicate and work with their child. Parents can help you understand a student’s unique strengths and areas they need more help. You could ask parents to complete AllPlay Learn’s strengths and abilities communication checklist under relevant resources below to find out more information about their child.

- Teach students to self-manage their behaviours. Use a collaborative process, which includes working with the student to select the target behaviour.

- Promote self-determination. Empower and teach students to make choices, set goals, be independent, and develop problem-solving abilities. Use technology as needed. For example, technology can be used by students who communicate non-verbally to indicate preference.

- Errorless learning-based teaching may be more effective than trial-and-error-based teaching for some students. During errorless learning, students are not given the chance to make any errors. Instructions are followed immediately with a prompt to minimise the chances of an incorrect response (e.g., pointing or highlighting the correct answer for students). Prompts can be removed systematically over time until students can independently respond correctly.

Curriculum considerations

- Drama and music classes let students participate with others in an environment that isn’t as dependent on academic skills.

- Consider providing lots of small group activities. Choosing who will be in each group prevents a student with an intellectual disability from being left out or picked last.

- Teenagers with an intellectual disability may find literacy skills challenging. They may need one-to-one help using mnemonics (memory strategies) and flash cards, as well as lots of time to practise.

- Students with an intellectual disability can think about books (tailored for their reading level) on a deeper level with help from a teacher. Ask students questions about the book to get them thinking. Teach them to summarise the story or guess what might happen next. Consider breaking students into smaller groups to discuss and make meaning of the text. This could include students summarising, questioning, clarifying and making predictions about the text.

- Use self-regulated strategy development to help students with writing skills. First, present and discuss a writing strategy with students. Clearly model and help students understand and memorise this strategy (e.g., through a mnemonic device). Finally, support students to apply this strategy with increasing independence.

- Use phonic-based instruction. Teach students decoding strategies (e.g., associating letters with sounds, putting sounds together). Consider helping students memorise common, high-frequency words.

- Clearly explain and model the tasks and instructions. Break tasks into smaller components and model each step. Provide lots of opportunities to practise before proceeding to more difficult tasks and skills

- Students with an intellectual disability may need simple instructions, demonstrations and prompts to learn new skills in physical education classes. Demonstrations and prompts may need to be repeated lots of times.

- Skills may need to be broken down into smaller steps.

- Some students may need physical help with learning new tasks

- Consider using pair or small group activities. Choosing who will be in each group prevents students with intellectual disability from being left out or picked last.

- Some students may find changing in and out of their sports uniform at school difficult. Consider letting a student with an intellectual disability come to school in their sports uniform or give them extra time for changing.

- Students with an intellectual disability may benefit from support including one-to-one help, and instructions or information repeated lots of times.

- Students with an intellectual disability may find learning a new language difficult.

- Assess whether learning a language will be of advantage to them on a case-by-case basis.

- If they learn a language, focus on areas of strength and build from there. They may need one-to-one help, and instructions or information to be repeated lots of times.

- Students with an intellectual disability may experience delays with numeracy.

- Immediate positive feedback and correction can help, as can lots of time to practise.

- Some students with an intellectual disability will learn well through sensory learning. Present new concepts using various modes. Using visual supports, such as graphic organisers, can aid understanding and problem-solving.

- Consider providing clear and exact instructions in different strategies or methods for solving problems.

- Consider pairing a student with an intellectual disability with another student who can demonstrate maths skills and give instructions or help.

- See Consider adjustments to activities and rules (consider using time delay programs or approaches).

- Students with an intellectual disability may benefit from one-to-one help, and instructions or information repeated lots of times.

- Use clear language to explain tasks and instructions.

- Visual representations, such as graphic organisers, could be useful in helping students organise information and learn the connection between different concepts.

- See Consider adjustments to activities and rules (use systematic instructions).

- Students with an intellectual disability may benefit from one-to-one help, and instructions or information repeated lots of times.

Other considerations

First aid

Safety drills

Behaviour

Homework

Planning and organisation

School excursions or camps

Friendships

Transitions

Other co-occurring conditions

- A student with an intellectual disability may have difficulty communicating that they are in pain or unwell. Watch for signs of pain such as grimacing.

- Encourage gestures or other methods of communication to work out what may be happening.

- Some students with an intellectual disability may not know how to tell an adult if there is an emergency, or what to do in an emergency or emergency drill. Consider making time for demonstrating and practising what to do.

- Some students may not complete their work or they may engage in disruptive behaviour (e.g. call out during class). Giving students choices in their work may make them more motivated and less likely to be distracted. Showing them positive behaviour and giving them clear instructions so that they know what is expected can also help.

- Some students may not complete their work or they may engage in disruptive behaviour (e.g. call out during class). Giving students choices in their work may make them more motivated and less likely to be distracted. Showing them positive behaviour and giving them clear instructions so that they know what is expected can also help.

- Picture cards or stories about social situations can teach students about positive behaviour.

- Many students can be taught how to self-monitor their behaviour. Consider asking them to record whether they have done what they are asked to do. AllPlay Learn’s self-monitoring form can be found here.

- Refer to the ABC approach for more information on how to reduce challenging behaviour by supporting the young person and promoting more helpful behaviour, and our emotions page for more information about supporting a young person with managing their emotions.

- Consider student strengths and challenges. Some student may find working on school work at home without help difficult. Work out what a student is able to do without help when assigning homework. Alternatively, consider not giving homework to the class when possible to give the student some time away from books.

- Some students with an intellectual disability may find being organized for class challenging.

- Consider providing support with planning and organisation.

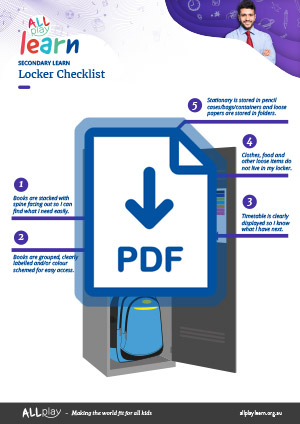

- See AllPlay Learn’s story how to be organised.

- Some students with an intellectual disability may need extra help on camps. Discuss with parents what help their child may need.

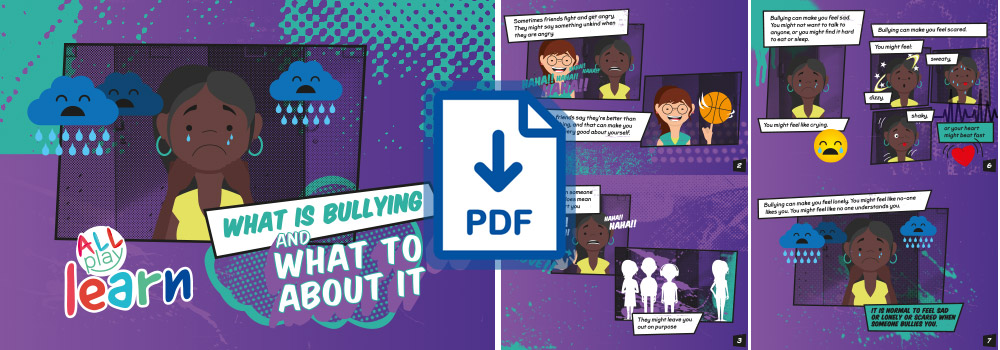

- A teenager with an intellectual disability may find understanding friendship difficult. Access AllPlay Learn’s story What is bullying and what to do about it under relevant resources below.

- Read more about the steps teachers can take to support a student who is being bullied or excluded at school.

- For more information about supporting students with disabilities when transitioning across education settings, access AllPlay Learn's transition page.

- Post-school transition to adult life should begin as early as possible in school.

- Aim to increase independence by working on organisational, social and problem-solving skills, and time- and self- management skills. Provide plenty of opportunities to practise them across a range of contexts.

- It may be helpful to identify skill gaps and develop a support plan to help them be successful (e.g. social skills, academic and/or employment skills).

- Some students with an intellectual disability may also be diagnosed with autism, ADHD, anxiety, cerebral palsy, or oppositional defiant disorder.

Relevant resources

Visit our resources page for a range of resources that can help to create inclusive education environments for students with disabilities and developmental challenges. Some particularly relevant resources for students with intellectual delay include: