Inclusive Language

to Strengthen Inclusive School Communities

The language we use is important.

A shared understanding and agreement on the inclusive language

a school community will use ensures all students receive a dignified,

meaningful education.

The language a school community uses about disability can influence

attitudes and impact people’s lives. When school communities speak

about others positively, using language that is preferred by students

with disability and their families, it contributes to an inclusive culture that

changes how students with disability are viewed by themselves and others, and

supports a sense of belonging.

What language do you use to talk about students with disability?

When it comes to specific terms for disability, student preferences and voice (and those of their family when appropriate) take priority. Encourage students with disability to speak for themselves, and use their preferred language.

Language that positions a student as a problem or object of pity or charity, is not helpful.

Instead, when speaking about students (or others) with disability, think of the student holistically. Focus on their interests, contributions, personality traits, and individual and inter-personal strengths.

Use the student’s name.

Only refer to disability when it is relevant.

Some students prefer a person-first approach.

This is where you refer to the person before the disability, for example ‘student with cerebral palsy’. This puts the focus on the student, rather than their disability.

Others may prefer identity-first language.

For example, ‘disabled student’ rather than a ‘student with disability’. This can help individuals to claim their disability with pride.

Respect the diverse preferences of students.

This may mean using different terms for individual students in line with their personal preferences (for example, Marley is on the autism spectrum; Kyan has ADHD), and when discussing disability more broadly, using a term that most students are comfortable with (for example, ‘We have recently implemented a new approach to better support autistic students’).

Keep in mind that cultural groups may have different beliefs about disability.

For example, there is no comparable word for disability in Aboriginal languages, and many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with disability do not identify as a person with disability. This is important to remember when working with the student or their family.

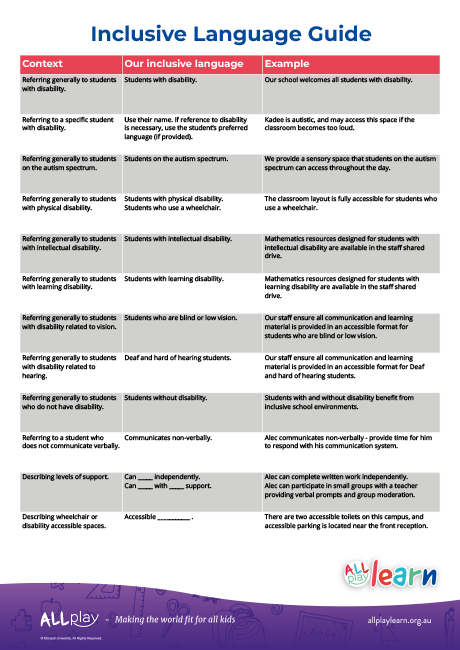

Terminology

Consider using the guide below to think about recommended language and the language preferred by the student and/or their family. You may note this down in the handout provided below. The terms below are not a fixed set of what is right and preferred language can change.

- student with disability

- has disability

- student who uses a wheelchair

- student with quadriplegia

- student with paraplegia

- student with physical disability

- physically disabled student

- wheelchair user

- student with cognitive disability

- student with intellectual disability

- student with learning disability

- diverse learner

- student on the autism spectrum^

- neurodivergent

- autistic^

- blind (if they identify that way)

- Deaf (if they identify that as part of the Deaf community)

- deaf (if they do not identify as part of the Deaf community)

- student with a vision impairment

- student with a hearing impairment

- student who is hard of hearing

- student without disability

- neurotypical

- ADHD

- lived experience of ADHD

- ADHD with predominantly inattentive/hyperactive/combined presentation

- communicates non-verbally^

- non-speaking student

- communicates using

- student with complex communication needs

- accessible toilets/parking

- symptoms, traits or characteristics

- may not self-regulate all the time

- may need support, scaffolds or guidance to …

Adapted from:

- People With Disability Australia. (2019). ‘What do I say? A guide to language about disability’.

- Brown & Quinn (2022). Talking About ADHD. AADPA: Australia. 'The People with Disability Australia guide was written by people with disability, and the AADPA guide was co-written by people with lived experience of ADHD'.

^Some students and/or their families may prefer this language, while others may not. Always ask a student and their family what language they would prefer you to use

Using strength-based language

- Explicitly identify a student’s strengths and what they can do. Many challenges can, in specific situations, also be a strength.

- Frame challenges in terms of external supports that may be needed.

- Identify a range of terms that can be utilised in place of deficit-based terminology.

Below are some examples that you may find helpful:

| Deficit-based language | Strengths-based language |

|---|---|

| She doesn’t adjust well to changes in routine. | She may follow routines and class rules well, as she tends to like things to be done in a particular way or order. |

| He doesn’t understand abstract concepts. | He tends to learn well with concrete, rather than abstract, examples. |

| They can’t apply a skill learned in one task to another context. | They benefit from support in using a skill they learned in one task in another context. |

| He becomes upset when plans change without warning. | He tends to be more comfortable when he is given warning about an upcoming change. |

| She struggles to follow instructions. | She finishes tasks quickly and with enthusiasm, but I have observed that at times she misses instructions. Are there strategies you use at home that might be helpful in the classroom? |

| His motor skills are underdeveloped, and he becomes angry and oppositional when we are completing craft activities. | He listens carefully to instructions and takes pride in his work. He becomes frustrated with work involving fine motor skills, and some additional supports or modified tools/activities will enable him to complete these activities to his satisfaction. |

| She needs support with small group work because she has low functioning autism and is non-verbal. | She can complete written work independently, and can participate in small groups with a teacher providing verbal prompts and group moderation. |

To learn how to incorporate a student’s strengths when developing strategies to support them in the classroom, view AllPlay Learn's Inclusive Questions. Teachers may access further examples and more by completing AllPlay Learn's Online Professional Learning Course.